The name Griselda Blanco still sends shivers down the spines of those familiar with Miami’s bloody cocaine wars of the 1980s. But while the Cocaine Godmother’s legend has been cemented in true crime documentaries and Hollywood adaptations, her son Uber Trujillo remains a shadowy figure whose tragic story deserves examination. Born into a world where violence was currency and loyalty could be purchased with blood money, Uber’s life exemplifies the devastating generational impact of organized crime.

Unlike his mother, who cultivated a reputation for brutality that would make hardened criminals flinch, Uber never sought the spotlight. Yet he couldn’t escape the criminal shadow that followed him from childhood through to his violent end in 2001.

Growing Up in Griselda Blanco’s Criminal Empire

Uber Trujillo entered the world sometime in the late 1960s, though exact records remain frustratingly vague—a common occurence for children born into criminal dynasties where documentation often takes a backseat to survival. He was the second of Griselda Blanco’s four sons, and from his earliest memories, normalcy was never an option.

While other kids worried about homework and playground politics, Uber and his brothers navigated a reality where armed bodyguards were as common as babysitters. The family’s wealth was staggering. Griselda’s cocaine smuggling operation between Colombia and the United States generated an estimated $80 million per month at its peak, according to law enforcement estimates from the Drug Enforcement Administration. That kind of money bought mansions, luxury cars, and political protection, but it couldn’t purchase peace.

The Trujillo household operated under rules that would seem absurd to most families. Trust no one outside the family. Never discuss business where you might be overheard. Always know where the exits are. These weren’t suggestions but survival strategies in a world where rivals didn’t just compete—they eliminated.

The Inescapable Pull of the Drug Trade

There’s a particular cruelty to being born into a criminal empire. You inherit wealth and excess, sure, but you also inherit enemies, paranoia, and a future that’s already been written in violence. Uber Trujillo experienced this firsthand as his mother’s reputation grew increasingly fearsome throughout the 1970s and 1980s.

Griselda Blanco wasn’t just another drug lord—she pioneered smuggling techniques that would become industry standard, including hiding cocaine in specially designed lingerie and the infamous “motorcycle assassinations” that later became a cartel trademark. Her innovation came with a body count that some investigators estimate reached upwards of 200 people, though the true number will never be known.

For Uber and his siblings, this wasn’t abstract violence shown on evening news broadcasts. These were real threats that materialized in kidnapping attempts, assassination plots, and the constant awareness that their last name made them targets. Court documents from Griselda’s various trials reveal that she moved her children frequently, employed multiple security teams, and even considered sending them to boarding schools in Europe under assumed names.

But the dangerous path had already been set. Growing up surrounded by the drug world’s wealth, witnessing the power it granted, and seeing how “normal” people treated his family with a mixture of fear and deference—all of this shaped Uber’s worldview in ways that made legitimate alternatives seem almost pointless.

Criminal Activities and Family Pressure

Unlike his mother, Uber Trujillo never achieved infamy in the drug trade. He wasn’t a kingpin, didn’t run major smuggling operations, and his name rarely appeared in DEA reports or court filings. Yet he was involved in criminal activities nonetheless, though the specifics remain murky due to sealed juvenile records and the code of silence that governed his world.

What we do know comes from fragmentary sources—testimony from former associates, occasional mentions in legal documents related to his mother’s cases, and retrospective accounts from journalists who’ve pieced together the Blanco family history. These sources suggest Uber worked on the periphery of the cocaine business, handling money laundering operations and occasionally serving as a courier when his mother’s organization needed someone family could trust absolutely.

The pressure of being Griselda Blanco’s son can’t be understated. In the criminal world his mother dominated, weakness was fatal and independence could be interpreted as betrayal. Former Miami Police Department detective Al Singleton, who spent years investigating the Blanco organization, noted in a 2008 interview that “those kids never had a choice—they were soldiers in their mother’s army from the moment they could walk.”

This wasn’t the romanticized mafia loyalty depicted in movies. This was survival wrapped in the guise of family obligation.

The Violent End in Mexico

By 2001, Griselda Blanco’s empire had largely crumbled. She’d served nearly two decades in federal prison and been deported back to Colombia. Her sons were scattered, attempting to rebuild lives or continue criminal enterprises without her protection. For Uber Trujillo, this meant relocating to Mexico, possibly seeking new opportunities in a drug trade that had evolved considerably since his mother’s heyday.

The circumstances surrounding Uber’s murder remain disputed. Some accounts place him in Medellín, Colombia, rather than Mexico—the fog of violence and misinformation that surrounds cartel killings makes definitive facts difficult to establish. What isn’t disputed is that he died violently, shot multiple times in what appears to have been a targeted assassination rather than a random act of violence.

He was approximately 33 years old.

The murder highlighted a grim reality about the drug world: debts and vendettas don’t expire, and being the Cocaine Godmother’s son meant carrying a target that never disappeared. Even with Griselda imprisoned and her organization dismantled, the enemies she’d made during her brutal reign hadn’t forgotten.

The Fate of Griselda Blanco’s Other Sons

Uber’s death wasn’t an isolated tragedy but part of a pattern that claimed all of Griselda Blanco’s children. His brothers met similarly violent ends, each murder reinforcing the deadly impact of their mother’s legacy.

Dixon Trujillo, the eldest, was killed in Colombia in the early 2000s under circumstances that remain unclear. Osvaldo Trujillo died in prison in the 1990s, though conflicting reports suggest he may have been murdered on the outside. The youngest, Michael Corleone Blanco (named after the Godfather character), survived into adulthood and has since attempted to legitimize himself through reality television and a clothing line that capitalizes on his mother’s notoriety.

Michael’s survival is notable precisely because it’s so rare. Children born into high-level drug trafficking families face mortality rates that would shock most people. A 2015 study examining the fates of children of major Colombian cartel figures found that over 60% died violently before age 40.

Cultural Impact and Media Portrayals

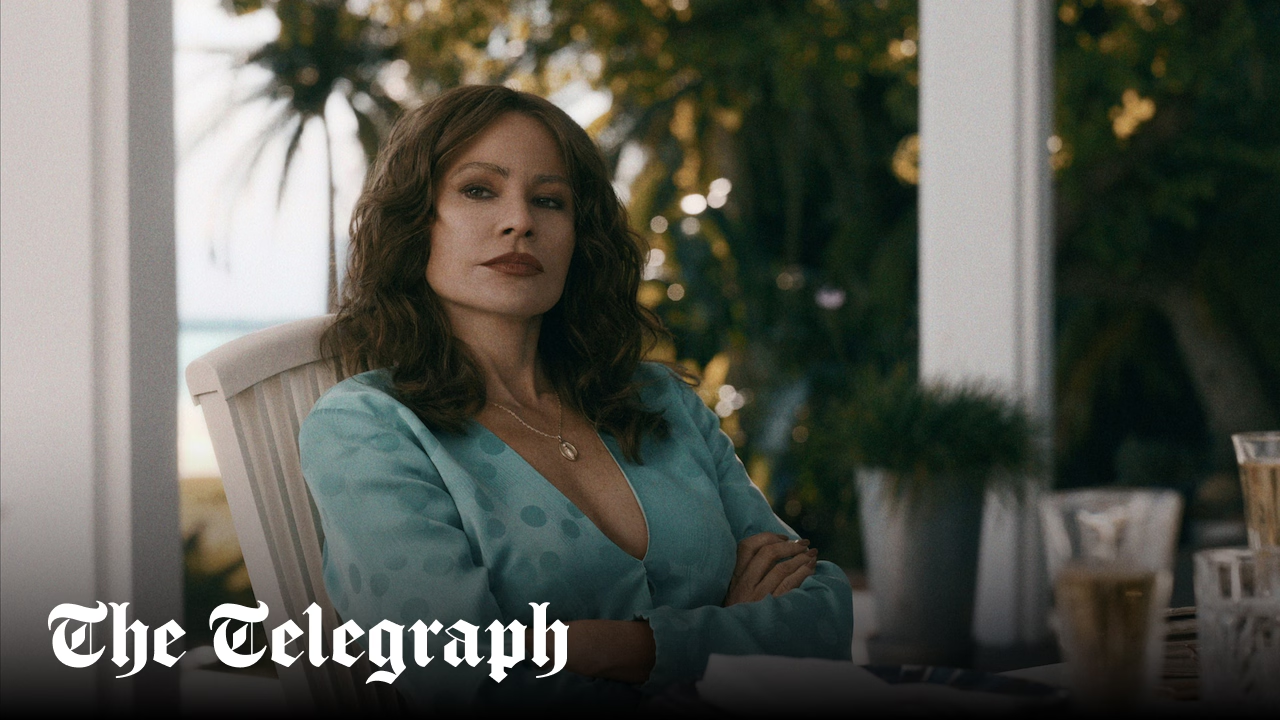

The Blanco family story has proven irresistible to filmmakers, journalists, and true crime enthusiasts. Catherine Zeta-Jones portrayed Griselda in a 2018 Lifetime movie, while Netflix released a high-profile series starring Sofía Vergara in 2024. These productions focus overwhelmingly on Griselda herself, with her children appearing as supporting characters or cautionary footnotes.

This imbalance is unfortunate because Uber Trujillo’s story—and those of his brothers—illustrates something documentaries about drug lords often miss: the generational trauma and inevitable violence that organized crime perpetuates. Books like “The Godmother: The True Story of the Hunt for the Most Bloodthirsty Female Criminal of Our Time” by Richard Smitten provide more context, though even these comprehensive accounts struggle to penetrate the secrecy surrounding the family’s private life.

What emerges from these cultural references is a portrait of waste. Uber had opportunities most people never receive—wealth, education options, the ability to go anywhere and become anything. Yet the circumstances of his birth made those opportunities nearly impossible to access. The criminal world doesn’t easily release its children.

Legacy: A Cautionary Tale About Organized Crime

Uber Trujillo’s legacy isn’t measured in drug shipments moved or territories controlled. Instead, it serves as a warning about the true costs of the drug trade—costs that extend far beyond arrest statistics and seizure amounts to encompass destroyed families, wasted potential, and cycles of violence that persist across generations.

His mother’s criminal empire generated staggering wealth but provided nothing of lasting value. The mansions were seized, the money laundered into untraceable accounts that benefited strangers, and the power structure collapsed the moment Griselda went to prison. What remained was violence, instability, and a body count that included her own children.

Former federal prosecutor Luis Perez, who worked on cases involving the Blanco organization, reflected in a 2010 interview that “Griselda destroyed everything she touched, including her own sons. They never had a chance at normal lives, and they paid for her choices with their blood.”

This isn’t to absolve Uber of responsibility for his own criminal activities. He made choices, even if those choices were constrained by circumstances most people will never face. But understanding his story requires acknowledging how thoroughly the drug world entrapped him from birth.

Lessons From a Forgotten Life

Perhaps the most striking aspect of Uber Trujillo’s story is how thoroughly he’s been forgotten. While his mother remains a fixture in true crime discussions, spawning books, movies, and endless debate, Uber barely merits footnote status. Yet his life illuminates truths about organized crime that sensationalized cartel documentaries often miss.

The drug trade doesn’t just destroy users or claim casualties in turf wars. It devours families, making criminals of children before they’re old enough to understand what’s happening. It creates cycles of violence that persist long after the original players are dead or imprisoned. And it leaves behind wreckage—human and otherwise—that society rarely acknowledges.

Uber Trujillo died at 33, murdered in circumstances that remain unclear, leaving behind no known children and little public record of his existence beyond his connection to his infamous mother. His brothers met similar fates. Their deaths didn’t make headlines or spark public outcry. They were simply more casualties in a war that’s claimed hundreds of thousands of lives and shows no signs of ending.

If there’s meaning to be found in Uber’s forgotten life, perhaps it’s this: the glamorization of drug lords and cartel culture obscures the reality that these organizations destroy everything they touch, starting with their own families. The Cocaine Godmother’s throne was built on corpses, including those of her own children.

That’s not power. That’s annihilation.